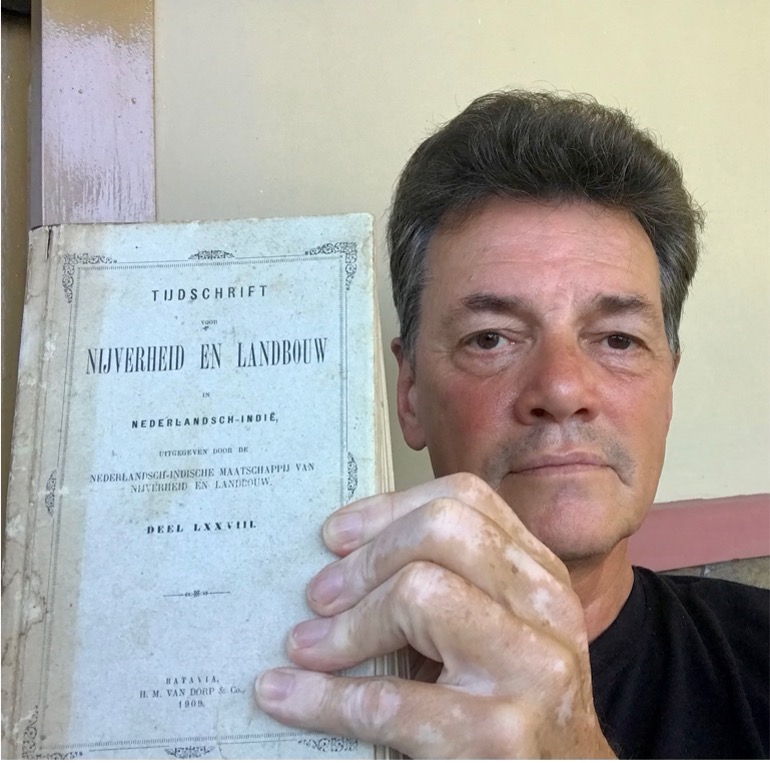

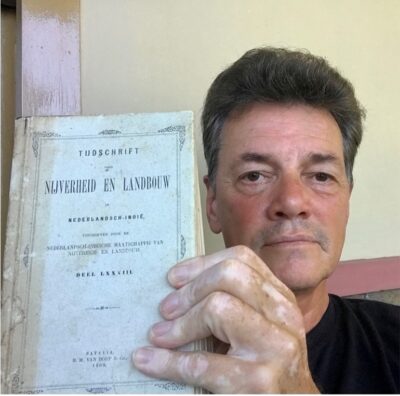

I was sitting at my terrace in North Sulawesi on a Saturday morning and reading another old Dutch publication from 1909 about all the potential our land offers and so many wise lessons about managing the land to keep it productive.

I was sitting at my terrace in North Sulawesi on a Saturday morning and reading another old Dutch publication from 1909 about all the potential our land offers and so many wise lessons about managing the land to keep it productive.

Book ‘Nijverheid en Landbouw’

I like to read these old publications, written in a direct style and very factual. Like in this 739-page 112-year-old book written in somewhat archaic Dutch, there are so many treasures in them. When I try to look online for these books from the Dutch colonial era, I cannot find them in the library of congress. But when I look amongst the 25 million books that Google has already scanned, out of the estimated 130 million books published in human history, I find a few scans of the same publication from some other years but not this 78th edition. Not that this one is of more interest than other editions, I just researched whether these historical documents have become accessible through all present search engines. Now everybody can just take a picture and convert it into a text file that can be instantly translated to almost any language. The opportunity is there. I wonder if I could find out how often readers actually access these scanned books?

Most extensive collection of original books on the Minahasa

Our Masarang Foundation has probably the world’s most extensive collection of original books on the Minahasa. This part of North Sulawesi is known for culture, language, traditional laws and grey literature. Several of those have probably never been scanned and uploaded. The specially built air-conditioned library (to prevent the books from damage by decomposing fungi that thrive in the high air humidity of the higher altitude Tomohon location) also functions as an education room and can be used for meetings or workshops. Unfortunately, very few students or researchers still come to our public library to access the unique collection of local know-how. Reading from the ubiquitous smartphones has led to physical libraries everywhere getting fewer and fewer visitors. People also seem to be overwhelmed with an unlimited number of subjects, while time spent on one topic appears to be measured in minutes rather than months or years to get a good understanding of an issue.

Tiktok versus wandering through the fields

When I see my three-year-old grandchildren flipping through games, Instagram pictures and TikTok clips at neck-breaking speeds, I feel really old. I spent my youth wandering through the fields, identifying birds, observing owl behaviour, reconstructing skeletons for hours, days and voraciously reading factual books. Until today I still come up with the best insights and inspiration while walking in nature and just taking enough time for ideas to well up. It seems nowadays only some researchers can still afford the time to observe in the way Darwin did.

Do we want to learn?

Times are changing, yes, I know. But the fundamental laws of nature are not. And the observations of our predecessors are as valid today as they were then, if not more so. When I read about the fate of the Sumatran elephants from 1931-1938 in another old publication, I think why are we still discussing how to solve the same problems when the basic issues and answers are still the same as they were a hundred years ago?The real problem is, do we want to learn and draw the logical consequences of what science teaches us and convert it into actual action? The Internet can provide all the tools to access the facts, old and new. This generation is the first and will be the last generation that has the ability and opportunity to change the downward spiral our world is in now. Hence the title “when will we learn”. Nature does provide us with the answers, and we still have a chance to fix our unsustainable ways. The work of Masarang shows that we can restore water, health, income and even the climate.The pandemic, with all its restrictions, gives us more time to think. Let’s hope more of us do and act upon it.

Willie SmitsTomohon, 24-7-2021